BL Labs and AHRC Digital Transformations

Last week I attended an event, organised by BL Labs working with the Arts and Humanities Research Council, at the British Library's Centre for Conservation. The event, described as a showcase event for British Library Labs and AHRC Digital Transformations, consisted of a packed series of presentations - I won't describe them all (and I missed Bill Thompson's talk anyway) but will, instead, pull out some snippets which interested me in particular.

Last week I attended an event, organised by BL Labs working with the Arts and Humanities Research Council, at the British Library's Centre for Conservation. The event, described as a showcase event for British Library Labs and AHRC Digital Transformations, consisted of a packed series of presentations - I won't describe them all (and I missed Bill Thompson's talk anyway) but will, instead, pull out some snippets which interested me in particular.

BL Labs

In introducing the event, Caroline Brazier (Director, Scholarship and Collections at the British Library) described the purpose of BL Labs as being an investigation into what happens when the British Library's large digital collections are brought together with enquiring minds in pursuit of digital scholarship.

Later on, Mahendra Mahey (a former colleague of mine) who manages the BL Labs project added some details - the BL Labs is a two-year Mellon-funded project to conduct research and development "both with and across" the British Library's digital collections. It does not do any digitisation, only working with existing digital collections. BL Labs has worked with a variety of people already, from those who were winners in a competition designed to solicit new ideas, to others who have simply turned up with an interest in working with the data. BL Labs is very interested in figuring out how the British Library can work with digital scholars and in pursuing this, also aims to discover new approaches to digital scholarship.

An interesting aspect to BL Labs has been their approach to selecting which of the 600+ digital collections they would work with. Limited resources meant that it would have been impractical to try to support people working with any and all of these. The criteria used to filter these to a more manageable subset were, in order:

- if the collection was copyright-cleared or not

- whether or not the collection was or had been curated (the project team felt the need to understand how the collection had been formed/developed)

- the state of available metadata for the collection

- the accessibility of the collection

Mahendra emphasised two important lessons that the BL Labs team have learned as a result of their activities:

- the importance of getting the curators of the collections involved in the BL Labs competition and events in order to properly understand and present the data

- the importance of releasing the data as early as possible since, as researchers start to engage with the data their research questions tend to change.

Later on Adam Farquhar (Head of Digital Scholarship at the BL) emphasised how the BL now has Digital Curators.

An aspiration of the BL Labs team is to develop a'top-level' gateway to BL digital collections at http://data.bl.uk, but this does not yet exist.

Mahendra's colleague, Ben O'Steen (Technical Lead at BL Labs) briefly demonstrated his innovative Mechanical Curator. Some years ago, Microsoft partnered with the BL to digitise 65,000 books. The majority of this collection is from the late 19th century, and the data is now public domain. The Mechanical Curator extracts "small illustrations and ornamentations" from these books and publishes them on a blog, creating a collection of often overlooked resources. You can read more about how this works on the BL's Digital Scholarship blog.

Scholarship driving the development of new tools

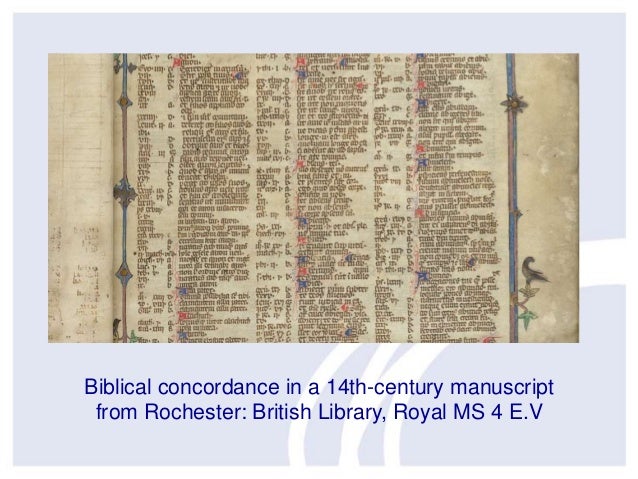

Professor Andrew Prescott gave a interesting talk on how arts and humanities are being transformed through digital scholarship. He used the example of a "biblical concordance" from the fourteenth century - essentially an early example of an index allowing one to look up terms and find occurrences of them throughout the text (apparently this innovation helped drive the adoption of numbered 'verses' in the bible). The point that Andrew illustrated is that this represented an enormous advance in scholarship. He invited us to consider how we ought to characterise such intellectual output, describing it as:

Professor Andrew Prescott gave a interesting talk on how arts and humanities are being transformed through digital scholarship. He used the example of a "biblical concordance" from the fourteenth century - essentially an early example of an index allowing one to look up terms and find occurrences of them throughout the text (apparently this innovation helped drive the adoption of numbered 'verses' in the bible). The point that Andrew illustrated is that this represented an enormous advance in scholarship. He invited us to consider how we ought to characterise such intellectual output, describing it as:

an enormous scholarly achievement in itself, but seen as a tool - wide ranging in its impact, but difficult to pin down.

Andrew went on to suggest that as the humanities and arts embrace digital scholarship, we should anticipate and encourage the development of new tools and approaches. He contrasted the sort of approaches taken to studying a letter from Gladstone to Disraeli, with the available archive of email messages - some 200 million of them - in the George W Bush Presidential Library. According to Andrew, there is no longer an easily identifiable set of methods that one might apply to scholarship in the digital humanities and arts: there is an increasing variety of formats, other disciplines are being introduced, and techniques are now ad hoc. He also pointed to a stronger connection to "practice-led" research, especially in the arts.

Andrew's presentation was illustrated with plenty of interesting projects. I'll briefly note a few (those which piqued my interest) here:

- a visualisation of languages used across London during the Olympic Games, 2012

- the Historical Thesaurus of English - showing the relationships between words over time

- Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE) - data relating to all the recorded inhabitants of England from the late sixth to the late eleventh century

- People of Mediaeval Scotland - database of all known people of Scotland between 1093 and 1314

- Old Bailey Online - a collection detailing the lives of "non-elite people"

- Jekyll 2.0 - recreating the experience of reading Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde in the 19C

Andrew's slides are available on Slideshare.

The Digital Panopticon

Sharon Howard (University of Sheffield) introduced this new 4 year international project which will examine the global impact of London punishments between 1780 and 1925. Using Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon as a neat metaphor for the project, Sharon described how two systems of punishment were run concurrently in this period: criminals could expect to be sentenced to transportation for seven years to life, or they could face a shorter incarceration in a London gaol. The Digital Panopticon will create a digital laboratory for investigating "power and human response", using criminal records.

Sharon quoted Michel Foucault, who said:

The Panopticon may even provide an apparatus for supervising its own mechanisms...

I'm not quite sure what this will mean in practice, but I am intrigued by the idea of applying the all-seeing, monitoring eye of the Panopticon to human behaviour in this way, using historic data rather than real-time surveillance.

Conclusion

It was interesting to see how the British Library is experimenting with digital curation. I have been aware of the growing interest and momentum in the so called digital humanities for some time. The projects described at the showcase event illustrated the range, extent and potential of the exploitation of structured data in digital scholarship in the humanities and arts. I think the significant message for me would be that data changes scholarship very directly - that as data becomes available, so the research questions themselves are changed.

Thanks to Mahendra, Ben and the rest of the BL staff who helped put on an interesting event.